On the last night of their lives, Jagdish Patel, his wife, and their two young children attempted to enter the United States through a nearly vacant stretch of the Canadian border.

Wind chills reached below 36 Fahrenheit (minus 38 Celsius) that night in January 2022, as the Indian family walked to meet a waiting van. They strolled through large farm fields and massive snowdrifts, navigating in the darkness of a nearly-moonless night.

The driver, waiting in northern Minnesota, texted his supervisor, “Please ensure that everyone is dressed for the blizzard conditions.”

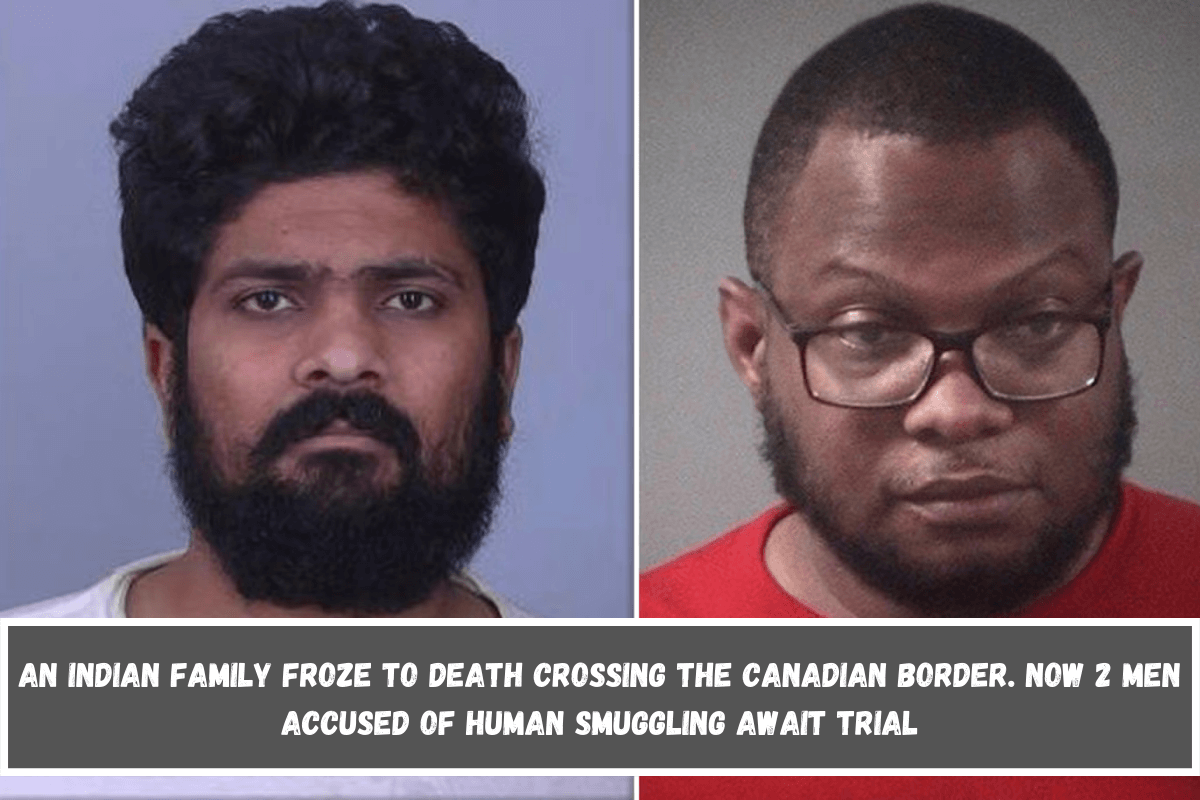

According to federal authorities, Harshkumar Patel, an experienced smuggler known as “Dirty Harry,” was in charge of coordination in Canada. According to authorities, on the US side was Steve Shand, a driver recently recruited by Patel at a casino near their Florida homes.

The two men, whose trial is set to begin Monday, are accused of participating in a sophisticated human smuggling operation that fed a rapidly rising number of Indians residing illegally in the United States. Both have pled not guilty.

During the five weeks the two worked together, documents submitted by prosecutors indicate they frequently discussed the terrible cold as they carried five groups of Indians across that peaceful section of border.

“16 degrees cold as hell,” Shand messaged during a previous trip. “They going to be alive when they get here?”

On the final journey, on January 19, 2022, Shand was supposed to pick up 11 more Indian migrants, including the Patels. Only seven people survived.

Later that morning, Canadian officials discovered the Patels, who had died from exposure to cold.

Jagdish Patel’s icy arms held the body of his 3-year-old son, Dharmik, wrapped in a blanket.

The small lanes of Dingucha, a sleepy village in the western Indian state of Gujarat, are littered with advertisements to relocate abroad.

“Make your dream of going abroad come true,” one banner states, citing three enticing destinations: “Canada. Australia. USA.”

This is when the family’s perilous journey started.

Jagdish Patel, 39, grew up in Dingucha. He and his wife, Vaishaliben, who was in her mid-30s, lived with his parents while raising their 11-year-old children Vihangi and Dharmik. (Patel is a common Indian surname; they are not related to Harshkumar Patel.) According to local press, the pair worked as schoolteachers.

The family was rather well-off by local standards, residing in a well-kept two-story home with a front patio and a large veranda.

“It wasn’t a lavish life,” said Vaibhav Jha, a local journalist who spent several days in the village. “But there was no urgent need, no desperation.”

According to experts, illegal immigration from India is fueled by a variety of factors, including political repression and a faulty American immigration system that can take years, if not decades, to lawfully negotiate.

However, much is based on economics, and how even low-wage positions in the West can spark optimism for a better future.

Dingucha’s expectations have shifted.

Today, so many villagers have gone overseas — officially and illegally — that blocks of homes are abandoned, and those who stay have social media feeds full of old neighbors showing off their houses and cars.

That encourages even more individuals to depart.

“There was so much pressure in the village, where people grew up aspiring to the good life,” Jha told me.

Smuggling networks were happy to help, charging payments of up to $90,000 per person. According to Jha, several families in Dingucha were able to pay this by selling acreage.

Satveer Chaudhary, a Minneapolis-based immigration attorney, has assisted migrants who have been exploited by hotel owners, many of whom are Gujaratis.

Smugglers with ties to the Gujarati business sector, he claims, have established an underground network that brings in laborers eager to work for low- or even no pay.

“Their own community has taken advantage of them,” Chaudhary explained.

The pipeline of illegal immigration from India has long existed, but it has risen dramatically along the US-Canada border. The United States Border Patrol arrested almost 14,000 Indians on the Canadian border in the fiscal year ending September 30, accounting for 60% of all arrests along that border and more than ten times the number two years prior.

The Pew Research Center projects that by 2022, there would be more than 725,000 Indians living illegally in the United States, trailing only Mexicans and El Salvadorians.

In India, investigating officer Dilip Thakor stated that while media attention resulted in the arrest of three persons in the Patel case, hundreds of similar instances never make it to court.

With so many Indians attempting to enter the United States, smuggling networks see no reason to discourage consumers.

“They convince individuals that it is quite easy to cross into the United States. “They never tell them about the dangers,” Thakor remarked.

US authorities claim Patel and Shand were part of a large enterprise that scouted for business in India, obtained Canadian student visas, arranged transportation, and smuggled workers into the United States, primarily through Washington state or Minnesota.

Patel, 29, and Shand, 50, will appear in federal court in Fergus Falls, Minnesota, on Monday to face four counts of human smuggling apiece.

Patel’s lawyer, Thomas Leinenweber, told The Associated Press that his client came to America to escape poverty and establish a better life, but “now stands unjustly accused of participating in this horrible crime.”

Shand’s attorneys did not respond to calls requesting comment. Prosecutors say Shand told investigators that Patel paid him around $25,000 for the five trips.

His last passengers, however, never made it.

By 3 a.m. on January 19, 2022, the 11 Indian refugees had spent hours walking in the snow and cold, attempting to locate Shand. Many were wearing jeans and rubber work boots. Nobody donned proper winter clothing.

Shand, however, was trapped. Prosecutors say he was driving to the pickup place in a leased 15-passenger van when he crashed into a ditch about a half-mile (0.8 kilometers) from the border.

Eventually, two migrants discovered the van. A passing pipeline worker eventually hauled the truck out of the ditch.

Soon after, a US Border Patrol agent on the lookout for migrants after boot prints were discovered near the border pulled over Shand.

Shand insisted there was no one else outside, even as five additional desperate Indians approached the truck from the fields, one of whom went in and out of consciousness.

They’d been walking for over 11 hours.

There were no children among the migrants, although one man had a rucksack with toys, children’s clothes, and diapers. He explained that a family of four Indians had begged him to hold it since they needed to carry their little son.

They had parted ways sometime during the night.

Hours later, the Patels’ remains were discovered just inside Canada, in a field near where the migrants had entered the United States.

Jagdish was holding Dharmik, with daughter Vihangi close. Vaishaliben was a short walk away.

Hemant Shah, an Indian-born businessman living in Winnipeg, about 70 miles (110 kilometers) north of where the migrants were discovered, helped organize a virtual prayer service for the Patels.

He’s used to harsh winters and can’t imagine the hardship they faced.

“How could these people have even thought about going and crossing the border?” Shah said.

Greed, he added, had killed four people: “There was no humanity.”

Leave a Reply