Decky Mbala moved to Maine with her daughter in 2021. They were both from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Like many asylum seekers who are originally not allowed to work in the U.S., she lived off of General Assistance.

Mbala stopped getting state and local help that paid for basic things the day she got her first paycheck. She didn’t know how she would pay her $1,300 rent for her Biddeford flat without it.

When her income just goes above certain limits, she hits what is known as the “benefits cliff.” This is when her public help suddenly drops.

“I had no idea what to do or who to turn to after GA left me.” A interpreter was used to talk to Mbala, who said.

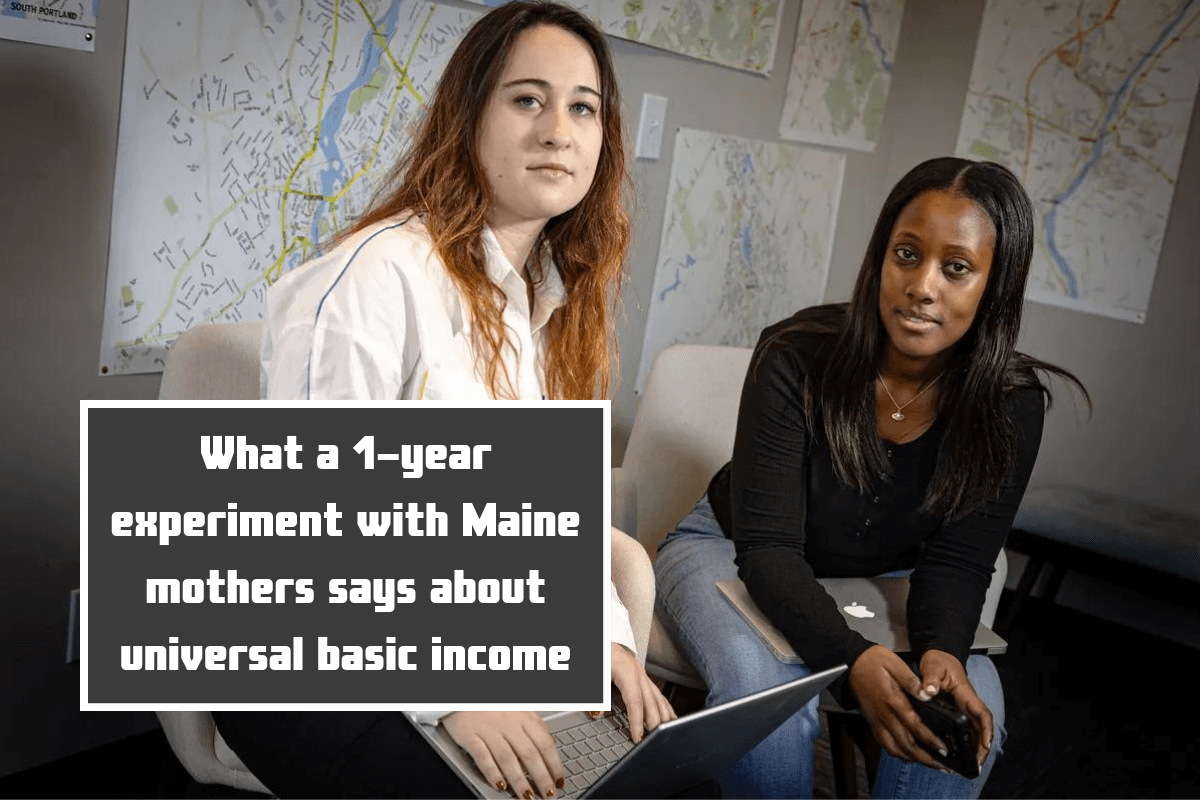

Then, M bala was one of 20 single mothers with low incomes chosen to take part in a test program called “Project HOME Trust.”

The one-year study looked at what would happen if these women, who were mostly asylum seekers and refugees, were given $1,000 a month with no strings attached. The women were compared to women who were in a control group and did not get the money.

It’s hard to say if a universal basic income scheme would work for most people in Maine because the sample size and time frame are so small. There isn’t one in any country, but many have tried it.

But most of the women’s lives got better, which is in line with other studies done across the country, though conservative groups have attacked one for making people work less.

The people who took part in the Project HOME study actually worked more hours each week on average. Not a single person in the program or the control group said they were “doing OK or better” financially at the start.

By the end, about half of the people who took the program had given that answer. The people in the control group had not changed. At the end of the study, participants were better able to handle an unexpected $400 bill, and their kids said they were happy. All stayed in their homes.

The Quality Housing Coalition, a Portland-based organization that runs the program, says these results show that Maine’s public benefits system needs to be completely rethought.

Starting this month, the coalition will do the one-year study again with 20 more moms. It is thinking about starting bigger programs in more rural parts of Maine in 2025.

For many years, we’ve had an unworthiness-based approach to public benefits that creates a lot of stigma, is really hard, and keeps people from thriving.

Victoria Morales, QHC’s executive director and a former Democratic state legislator, said that this is a shift to a trust-based approach.

Likely, a bigger version of this kind of program won’t start any time soon. The Maine Legislature has talked about this problem twice, but both times they chose to study it.

The state housing body, MaineHousing, has said that it does not run any programs like this right now and has no plans to start next year.

A large amount of money would be needed for such a scheme. The 20-person, one-year classes cost almost $500,000 in donations and grants that QHC had to get for them to run twice.

Garrett Martin, CEO of the liberal Maine Center for Economic Policy, said, “Doing something statewide could be very expensive depending on how many people you’re talking about.” The center has called for a state agency to run a cash assistance program.

Martin said that there are a “constellation” of programs that give money to families. Most of these are tax codes and welfare programs.

To make those resources more widely available, the federal government would have to get involved. Also, many of them will still want control and oversight over how public benefit programs are run.

Some people who support guaranteed income say that direct cash assistance programs with fewer spending limits would be more cost-effective, cut down on red tape, and help the business by giving Mainers more money.

But those who are against it say it would be expensive and might not make people’s lives better in the long term.

As Mbala continued to work at Cintas, she also started her own online business to sell clothes that she had created.

She said that was only possible because she had the direct cash to buy the tools she needed. She said she mostly spent the rest of the money on clothes for her daughter, flat furniture, and getting around.

Patience Munezero, who is 28 years old, had two 40-hour jobs before she joined the program. That meant Munezero wouldn’t see her 4-year-old daughter from Friday to Monday of every week because she worked full-time in a home for disabled people.

Munezero said that her daughter was so upset when she wasn’t there that she would have to keep her from daycare on Mondays.

Eight years ago, Munezero moved to Maine from Burundi. “This helped me change my life,” he said. “My daughter sees me more often, Saturday and Sunday after day care.” “I’ve learned to be happy and to value myself.”

Leave a Reply