Richard Keller is a history professor at UW-Madison and an expert on how climate change affects health. He says that he has been “joking with relatives in Texas as far back as 2003 that as their [climate change] problem was going to get worse, ours was going to get better.”

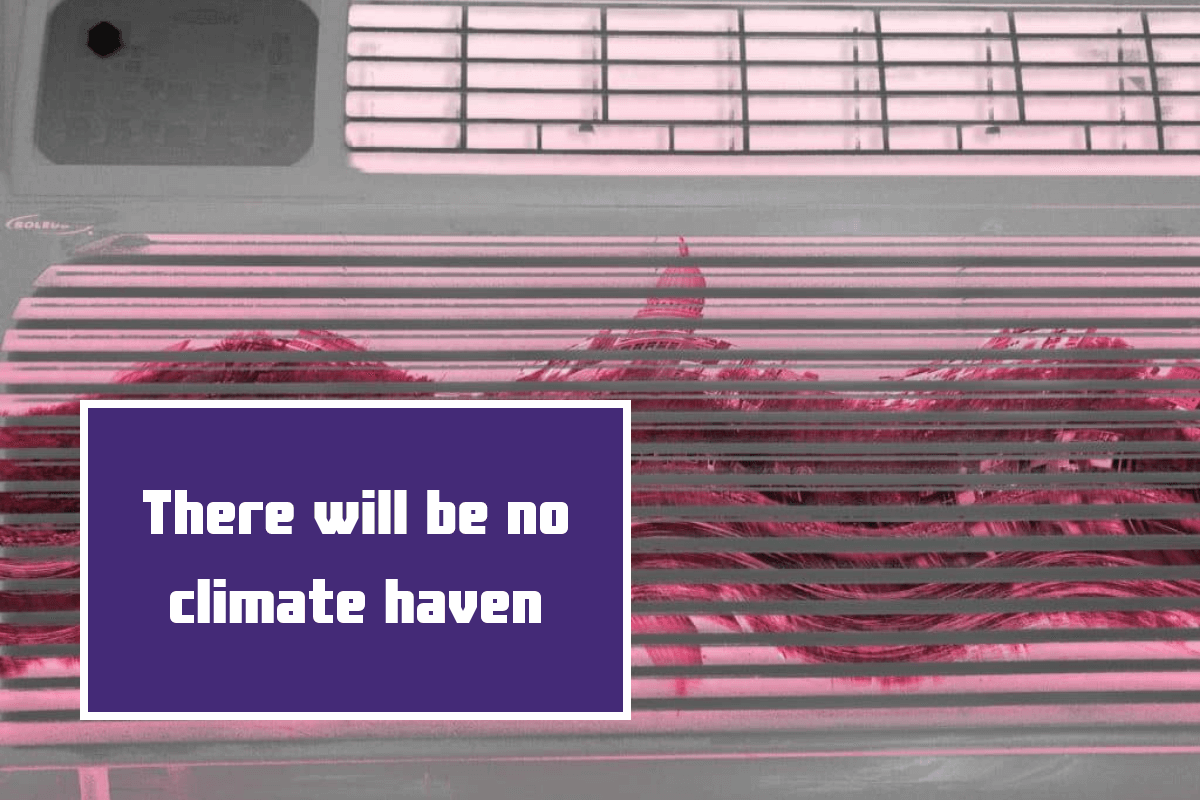

There is some truth to the idea that Wisconsin will be a “climate haven,” even though I’ve never been sure about it. Other areas will be affected much more quickly and severely.

More and more people will want to visit the Great Lakes area and its valuable freshwater supply. She says, “If you look at the cities that have grown the fastest in the US in the last 20 years, the vast majority of them are in places where climate change is a direct threat.”

Keller says, “So if you look at places like Arizona, California, and the Deep South, the climate problem is getting a lot worse every year.” “So much so that insurance companies are now saying that a city like Phoenix might not be livable in our lifetimes.”

The idea that Madison is a “climate haven” has been growing stronger over the last few years. Reports in the media, like a 2021 Spectrum News program, have supported the idea. Climate-aware officials, like Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway, have taken part in and then pushed those news stories, and so on.

Conservatives who don’t understand climate change can’t help but smell opportunism: Sen. Ron Johnson, one of the smartest people in our state, jumped on during a Senate budget meeting in April 2023.

Also, Destination Madison, which gets millions of dollars from the city, uses that story to market tourism to Madison and Dane County, which I think is pretty gross. Studies of migration in the U.S. show that people are moving not to so-called “havens” but to areas of the country that are more sensitive to climate change.

The story gives people a false sense of security and what seems like an easy way out of this problem instead of doing the hard work of cutting carbon emissions. In the summer of 2023, Wisconsin had a hot, dry time that hurt crops, and people all over the state were sick for a few weeks because of smoke from wildfires in Canada.

Some Native American forestry techniques help Wisconsin do a pretty good job of preventing and controlling wildfires. But smoke doesn’t care about borders, and neither does climate change.

Even though last summer wasn’t as bad, it still showed how many problems Wisconsin will have. Wisconsin is not going in the same direction as our southern neighbors, but the “climate haven” story is very flawed because of wildfires, floods and droughts caused by unpredictable rains, and, most importantly, extreme heat.

There are not enough homes in Wisconsin, especially in Madison. It will make a lot of slumlords happy, but telling the rest of the country to come over when it gets too hot in other parts of the country will only make things worse.

Also, from what I’ve seen, many homes in Wisconsin are designed for the winter, not the summer, and especially not the kind of summers we’re already having because of climate change.

“It was pretty clear as early as 1995 that colder places are more likely to be hurt by extreme summer heat than warmer places,” says Keller. More than 750 people died in three days during the heat wave in Chicago in 1995.

He says, “Most of us think of a cold city rather than a hot city.” Keller’s 2015 book, Fatal Isolation: The Devastating Paris Heat Wave Of 2003, looks at how over 1,000 people died in two weeks because their homes were too small, didn’t have enough air flow, and didn’t have air conditioning.

Keller says that we are also beginning to see this trend in Wisconsin, “where cities like Milwaukee are seeing more people go to the hospital during extreme heat waves during the hotter summers.” And because heat deaths aren’t always recorded, we might not even know how bad heat waves are.

When many of our old, cheap homes were first built, maybe a few decades ago, you could get through a Wisconsin summer by opening the windows and running an air conditioner during the hottest parts of the day.

These days, that’s not the case, and many low-income families have to choose between the cost of running their air conditioners and the damage the heat does to their bodies. During heat waves in 2022 that made it into the 90s in May, the big Madison landlord JSW Companies told its renters they couldn’t put in window AC units.

If someone has central air conditioning, they don’t have to worry about these cons (or the high power bills). They can even judge others for running their units. The power company in my area reminds people to save energy by setting their thermostats to 78 or even 76 degrees.

My temperature, on the other hand, hadn’t dropped below 78 since April until last weekend. It’s 80 degrees outside, but I’m cool and comfortable with a fan on.

People in Wisconsin seem to think that air cooling is more of a luxury than a necessity, but Keller says this is not true. “And I really believe that every summer proves that idea to be false.”

There is also the matter of rain. There’s no need to worry about sea level rise in Wisconsin, but have you seen our lakes lately? This is after a very dry year; lakes Mendota, Monona, and Wingra are all full to the brim. High temperatures make it more likely for water to evaporate, which makes clouds bigger and heavy. The clouds move more slowly when it rains, so they dump a lot more rain on a smaller area.

We will not have easy rains that fill up the lakes and water the plants. Instead, there will be either a flood or a drought. In reaction to the 2018 flood, the city made plans to reduce the risk of flooding. However, the isthmus is still just low-lying land surrounded by rising water. It’s not possible to do everything.

To be clear, both floods and drought can compact soil, which means that the soil is very close together and doesn’t have much air in it. When the ground is packed down, it’s harder to grow and for plant roots to spread out and take hold. The rain will make it harder for us to grow food no matter which way it goes.

People in Madison who support a “climate haven” like to gloss over all of this and focus on the fact that our winters are getting warmer instead. She told CBS News in 2021, “What we like to say here is that there’s no bad weather, there’s only bad clothing.”

It will be warmer in the winter, there will be enough fresh water, and the growth season will last longer. But that could also mean more mosquitoes and less stable growth seasons, which would be bad for crops. “It’s a mixed bag,” says Keller. Since climate change is also very hard to predict.

Keller also says, “Another problem is that we don’t know what will happen when our winters get warmer.” “That could mean that winters get much snowier or that springs get drier, for real.” There is no way to know what will happen. But because climate change is so uncertain, I don’t think we should think of a place as a single way to solve the problem.

When “climate havens” are offered as an answer, the main issue is that they are unfair. A lot of people in the southern US are barely getting by, and they don’t have the money to move to a different state. And that’s just in the US; there are problems all over the Global South as well. People who can move will be able to move poorer people from the north. Keller says, “It seems like a solution made for people who already have a lot of solutions.”

Rich people leave huge carbon tracks, while poor and middle-class people leave very small ones. For example, Ron Johnson’s private jet—which is actually owned by his children—has probably put more carbon into the air than I have in my whole life.

But, of course, those of us who don’t have much will be forced to live in places where the effects are worst and have to deal with the most trouble and chaos. We might split up as a country based on location, and “climate havens” won’t help most people.

Leave a Reply