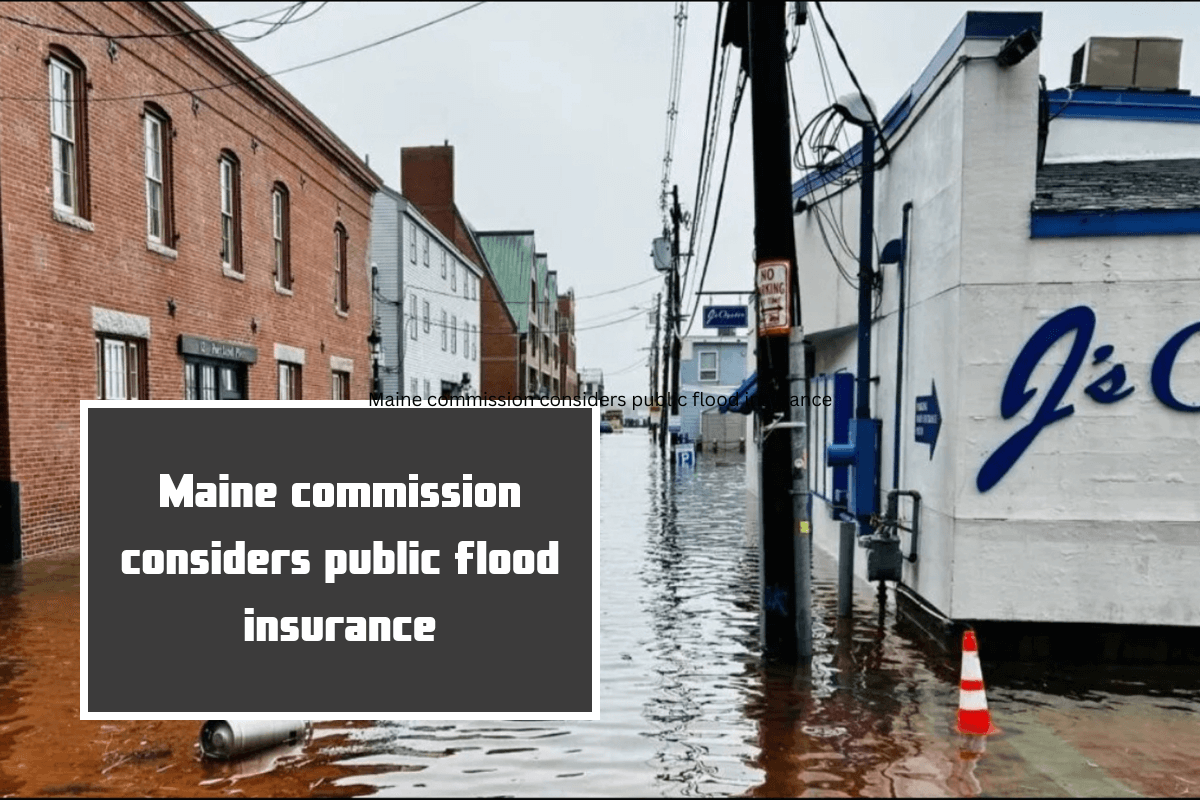

USA—Maine— The people in charge of reviewing Maine’s plans and reactions to natural disasters caused by climate change are at a crossroads.

In the past three years, Maine has had seven federal disaster declarations for severe storms and flooding. However, fewer people are signing up for nationally backed flood insurance policies across the state.

Public infrastructure, such as the working waterfronts on the coast, has been damaged many times, and the state has had to rely on federal emergency aid to rebuild and strengthen damaged infrastructure.

At a meeting earlier this month, the state Infrastructure Rebuilding and Resilience Commission discussed whether a public insurance choice could protect both people who don’t have insurance and the state’s public infrastructure.

Charlie Colgan, an economist and policy analyst at the University of Southern Maine, said, “It’s the only way I can think of that actually provides a permanent stream of funding… to respond… to disasters as they happen and the need for increased resilience.”

Collgan said, “Our own resources will have to do most of the work to make us resilient to climate change.”

Colgan brought up his plan at the meeting on September 4 and it includes a model for public insurance that is sparked by a state bond.

It’s not clear what would happen next. Colgan wants the insurance program to start out being only for public organizations, like cities and towns. These groups would pay into the pool and then get money out of it after disasters.

Payouts could also cover federal aid payments and general resilience projects, such as making culverts bigger.

Colgan thinks that if the program were made available to more people besides the public, it could also add an extra layer of safety for Maine property owners, acting as a cheap insurance option to fill in the gaps left by federally-backed flood insurance.

The Citizens Property Insurance Corporation is one of many insurance schemes in the U.S. that are paid for by the government. The Florida state legislature set up the non-profit public insurance company in 2002 as a “insurer of last resort.” However, policyholders have been very unhappy with the company.

Maine commissioners were excited when Colgan brought up the idea of a publicly-funded choice in early September. This was soon after the group gave a bleak picture of the state’s current insurance coverage.

A mere 1.3% of all houses and buildings in Maine are covered by the National Flood Insurance Program. This number has dropped by 25–30% since 2009, according to Peter Slovinsky of the Maine Geological Survey.

In the meantime, more and more claims are being made by Mainers who do have flood insurance. Bob Carey, Superintendent of the Maine Bureau of Insurance, says that Mainers have made 443 claims over the past 10 years, which have cost the state $16 million.

Carey said that 164 claims worth about $8 million came from just the last year, which is almost half of those claims.

Members of the commission didn’t have a good idea of what might be causing the drop in the number of homes and buildings that are insured by the National Flood Insurance Program. Slovinsky said that more homes could be owned outright, which would mean that people would not have to buy flood insurance like they do with most government backed mortgages.

Many people who don’t have to have flood insurance are choosing not to because the yearly premiums are going up or they don’t think the payout will be worth the cost. A number of people who made claims after last winter’s flooding told The Monitor that the money they got wasn’t always worth the trouble.

That was Gardiner business owner Stacy Caron in January, a month after her family’s pizza parlor was destroyed by water from the Kennebec River. “I mean, if you think for the past six years, we’ve spent $40,000 in flood insurance that hasn’t covered anything,” she said.

Policygenius, an online insurance marketplace, says that flood insurance plans paid out an average of $44,401 per claim across the country in 2021.

The low involvement rates in Maine were also linked by Colgan to insurance gaps that the commission has seen along the coast.

Privately owned wharfs in places like Stonington, Maine, are the backbone of the state’s coastal economy, but Colgan said that they don’t always have the insurance they need to get back on their feet after disasters like the floods in January.

“A lot of the important public waterfront facilities that were destroyed were private utilities,” said Dan Tishman, co-chair of the commission and head of Tishman Realty & Construction.

Linda Nelson, chair of the commission and head of economic and community development for Stonington, said that just over a dozen property owners in Stonington didn’t have flood insurance, which didn’t give them the money they needed to rebuild strong.

Neil Nelson said, “The things they thought [flood insurance] would cover couldn’t have been covered by [flood insurance].”

Nelson believed Colgan’s public insurance plan could help by bridging the gap between just rebuilding infrastructure that is at risk and making it stronger or moving it so it can withstand future storms caused by climate change.

Dan Tishman, co-chair of the committee and chairman of Tishman Realty & Construction, said, “A private owner might decide, ‘I can afford $40,000 for insurance, but I can’t afford $200,000, so I’m going to look for a layered approach.'”

Tishman said that they would then “be willing to pay into the layered approach if it was less expensive than trying to buy it through the capital markets.” This would build the insurance pool and lower the premiums of others.

The people on the commission seemed excited about the idea, even though it was still very new.

It is very worrying that the state is taking too long to adopt insurance and that the prices of resilience projects are going up. The commission needs to come up with specific policy ideas and funding sources by November.

Members came up with other, more doable ways to solve the insurance problem, such as funding a study to find out why fewer people are getting flood insurance, getting more cities and towns to join a government program that lowers flood insurance rates, and doing more general outreach.

But the insurance model was what people talked about, especially when they thought about how much money resilience projects would need.

Colgan said that the state’s finances were pretty good during last winter’s terrible flooding. However, the $60 million that Gov. Janet Mills set aside for resilience and recovery projects in this year’s supplemental budget won’t always be there, and it won’t be enough to stop the severe storms that are getting stronger and happening more often.

“How do we avoid not only the climate and weather disaster risks, but also the risks to the economy and the lack of resources to even begin to recover?” He asked Colgan.

Leave a Reply