Unanchored pill. Floor urine from pets. Dog feces on deck. Unknown “self-inflicted” injuries. Wood glue and six-inch screws in a play area. A bullet loose. Children were shown guns. A youngster in a roadside ditch.

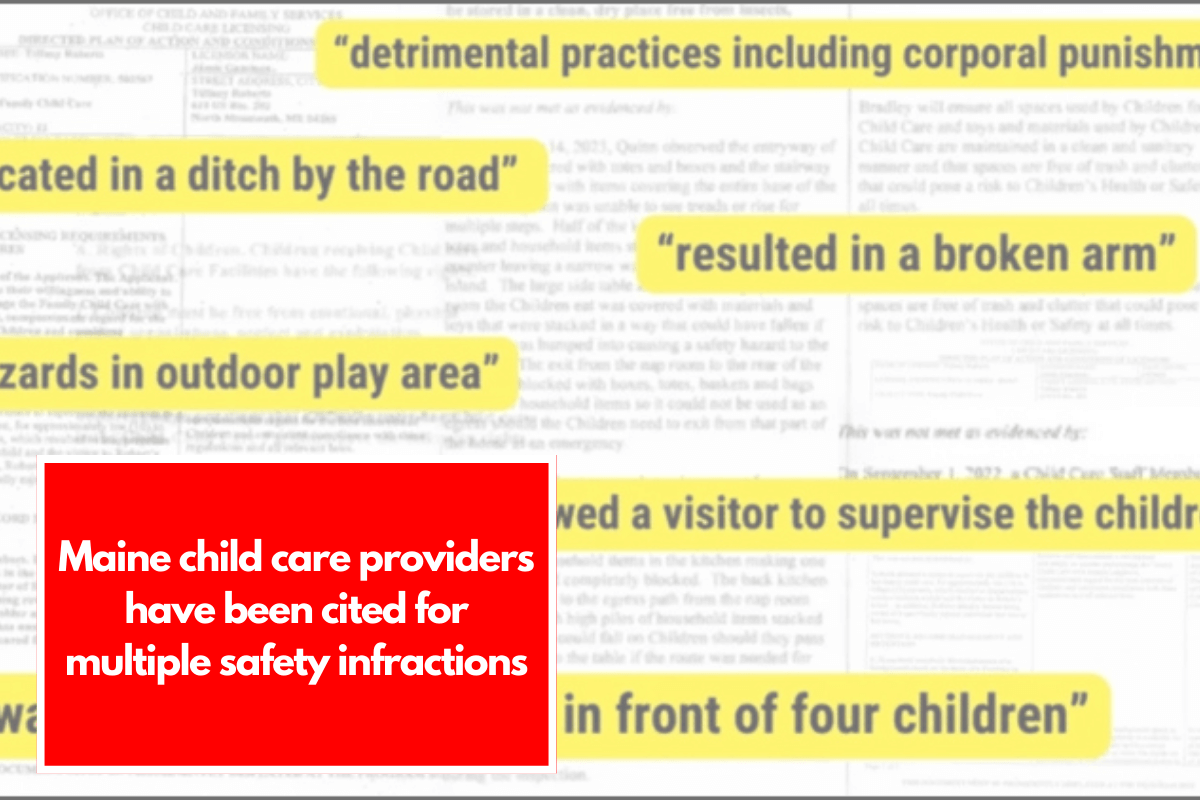

An investigation of thousands of records by The Maine Monitor and the Center for Public Integrity found those and other issues noted by regulators visiting child care providers around the state.

After visiting Cribs to Crayons in Bradford, 30 minutes northwest of Bangor, in 2022, inspectors noted that children saw a provider slam a kid against a wall and strike their head “loud enough for others to hear.”

Two years later, inspectors discovered many of the same issues: children reported being locked out alone outside, hit and grabbed by the chin, “body slam[med]” and pushed against cribs and the ground.

Inspectors noted that the provider yelled obscenities and that other children had witnessed her slap her child and wash their mouths with soap, which she later told regulators.

Cribs to Crayons has been inspected 21 times by the state since August 2021 and cited for 48 infractions.

Cribs to Crayons owner Courtney-Jo Arrants denies the charges and installed security cameras.

I left these youngsters with scrapes and bruises—where are the photos? The video where? Doctor’s appointment where? stated Arrants. The Monitor and Public Integrity found state inspection reports that quoted program youngsters who corroborated the incidents.

Cribs to Crayons received a conditional license, which requires providers to follow a “directed plan of action,” a formal order with particular requirements or standards before receiving a complete license.

In January 2024, Cribs to Crayons issued a conditional license and directed plan of action for one year. It required Arrants to complete training on “positive and constructive methods of Child guidance” within 30 days, “ensure only constructive methods of Child guidance are used,” and not subject any children to “an action or practice detrimental to the welfare of Children,” including “corporal punishment, shaming and embarrassment

Cribs to Crayons had to publish the state’s conditional license and letter “in public view,” and Arrants had to be examined by a “qualified professional” within 30 days to determine if she could safely care for children. Regulators briefly limited her license to six children from 12.

“It is awful that we are still having this conversation,” said District 17 Senator Jeff Timberlake, a government oversight committee member and child welfare advocate.

A decade ago, lawmakers lambasted regulators after inspectors found that a Lyman child care co-owner threw a child to the floor, ripped chairs out from under other children, and forced youngsters to put soap in their mouths.

Sunshine Child Care & Preschool received a conditional license after months of operation. Portland Press Herald reports say parents pulled their children and it closed.

This is well within the administration’s control. Timberlake said they need a hard chat to figure out why this keeps happening. “This kills children.”

Cribs to Crayons’ conditional license was withdrawn in August after inspectors found Arrants in accordance with state laws. The daycare is now completely licensed until August 2026.

The Maine Monitor and the Center for Public Integrity reviewed more than 6,000 inspection reports for 1,460 of Maine’s 1,500 child care providers and found that they have been repeatedly relicensed for transgressions like missing immunization records and leaving children unsupervised.

The data study covered 1,527 providers; those without website inspection reports were excluded.

Even though inspectors found facilities losing children and not recognizing they were gone, rubbish so high it obstructed exits, and firearms brandished in front of youngsters, the state has not revoked a single child care license since 2021.

DHHS has not revoked a license since 2021, but it has voided conditional licenses or denied licenses for twelve facilities during renewal for reasons including missing immunization records, inaccurate attendance, and providers withholding food, shaming children, or using derogatory remarks.

The 1,460 institutions have been cited for almost 16,000 breaches since 2021, but none have been fined.

“Licensing Action coupled with increased technical assistance and support has proven to be an effective strategy for compliance with regulations, whereas fines represent a punitive action that does not have the benefit of support from Licensing Specialists,” DHHS press secretary Lindsay Hammes wrote in an email.

Maine faces child care crisis

Maine, like much of the nation, is facing a child care crisis. The number of providers statewide has decreased by 23 percent in the past decade — from over 1,800 in 2013 to over 1,500 in 2024, a drop that has been particularly acute in rural areas.

The need for infant care is acute, with roughly 5,000 infant child care spots for the 10,000 to 12,000 babies born each year. Waitlists for care can stretch for years.

Experts attribute the rapid decline in child care providers in large part to the pandemic, when staff became reluctant to be exposed to the germs commonly found in child care facilities and sought higher-paying jobs in other industries.

Child care experts said many of the problems outlined in inspection reports could be attributed in part to staffing difficulties, as providers have struggled to compete for skilled staff as wages have risen elsewhere or have struggled to maintain enough staff for proper ratios.

A daycare can only raise fees so much before it starts losing families, who are often spending more on child care than they do on housing: annual costs for full-time care in Maine average between $8,580 for an infant to $11,960 for a toddler, according to Child Care Aware, which tracks costs nationwide. Many families spend much more than that.

“The fact is, you cannot run a quality program at all for family fees. You just can’t. We know that having one child in child care can be as much as your mortgage,” said Roy Fowler, acting director of Maine Roads to Quality Professional Development Network, a voluntary credentialing program.

The state has invested $15 million in financial and technical assistance to develop or expand child care programs, including facility renovation and enrollment. The “salary supplement system” in Maine receives about $30 million in state subsidies annually to supplement earnings for eligible providers.

Officials said earlier this year that they will enhance reimbursement rates for Child Care Affordability Program programs that help eligible families pay for child care. Rural and low-income counties will benefit most from the July reimbursement rate rise.

Heather Marden, co-executive director of the Maine Association for the Education of Young Children, said some facilities are using a less educated workers to keep expenses low for families.

“When you’re barely surviving with staff, you can’t work quality, right? Fowler said people only do what’s necessary to keep things functioning.

Firearms, missing children

State inspection records do not classify violations by kind or severity. A checklist of violations and a “inspection results” page allow authorities to describe particular violations.

The Monitor and Public Integrity classify violations as “safety violations” or “procedural violations” to distinguish administrative difficulties from situations that could harm a kid.

Safety violations include beating, shoving, tugging, or slapping; extreme unhygienic conditions; yelling or insulting remarks; a lack of monitoring; and gun or ammunition difficulties.

Procedure violations include missing records, not following norms, and not having emergency contact information.

Nearly 4,000 child care facilities in the state had safety infractions between 2021 and July, according to the Monitor of Public Integrity. State inspections must be public for three years.

These incidents include physical and verbal abuse, inadequate monitoring, children wandering away unobserved, serious sanitation issues, and failure to report concerns to parents or the department. Over 130 of these offenses constituted physical or verbal violence.

Maine has roughly 18 licensing specialists who work under the Office of Child and Family Services, a division within the Department of Health and Human Services that oversees licensing and inspections, and who are tasked with visiting all providers at least annually for an unannounced inspection. That’s more than the number of inspectors the state had a decade ago, when the facility in Lyman came under scrutiny.

Reports from inspections are publicly available online. Providers are also tasked with filling out incident reports for their own records as a way to formally document alleged transgressions for parents and the state to review.

Outside of the annual inspection, inspectors may interview staff, children, and parents and study video camera evidence to decide if a complaint is valid.

If an inquiry finds a complaint valid, regulators have numerous choices. If inspectors believe conditions “immediately endanger the health or safety of children,” state licensing laws allow regulators to request a District Court emergency license suspension.

In cases that “jeopardize the health and safety of children,” officials might suspend the program’s license for 10 days awaiting additional investigation.

Regulators may also provide a conditional license and a directed plan of action with timeframes for provider actions. State fines are possible.

The Monitor and Public Integrity identified thirteen incidences of state inspectors finding weapons, pellet guns, rifles, or pellets at child care centers across the state.

Several locations had unsecured ammo or weapons and ammunition stored together. Family-based providers can store firearms on the property, while center-based services cannot.

State papers show a household member “waved a rifle style-BB gun in front of four children, while yelling profanity and making threats against the provider,” at Tender Hearts child care in Sabattus. An incident report was never filed.

When police arrived for a family member incident, the provider did not disclose it, according to the inspection report. The agency learned of these instances during a complaint investigation.

After the state investigations, the department ordered Tender Hearts to “demonstrate a willingness and ability to operate and manage” the child care with “mature judgment, compassionate regard for the best interest of the children,” document all accidents, injuries, and incidents, and have a parent or guardian sign the document. The plan also requires the supplier to check all household members’ backgrounds.

Tender Hearts had to make all modifications immediately and publish the plan, and the department would conduct unannounced follow-ups to assure compliance.

In 2023, inspectors found owner Crystal O’Connor left three under-2-year-olds with her then-15-year-old daughter for appointments twice.

Tender Hearts’ complete license expires in January 2025.

O’Connor told The Monitor and Public Integrity that her son brought the rifle-style BB gun home and flashed it to the kids. She claims she requested a restraining order against him.

The report states that Roots to Grow in Waterville had more than 15 instances of excessive clutter and unsanitary conditions, including stacks of rubbish and debris up to four and five feet high that blocked exits.

A September 2022 inspection found the clutter so terrible that the inspector ordered the kids home “due to the dangerous conditions.” Roots to Grow has had roughly 50 safety infractions in three years, compared to Kennebec County’s two per child care center.

Roots to Grow had a conditional license until September, when state officials granted it a full license until 2026.

Roots to Grow received repeated phone calls, texts, and voicemails from the Monitor and Public Integrity. No one from the child care program responded.

A child care center in Trenton, a small hamlet outside Acadia National Park, has been cited for scores of breaches, several of which have been reported in the news.

Tiny Tikes staff informed inspectors they were “not allowed to comfort or hug a crying child,” and to ignore and lay them down in another room. A training handbook calls children “perps” and “criminals,” and inspectors uncovered a handgun in child care that was not disclosed.

Tiny Tikes has over 27% of Hancock County’s safety breaches.

The charges are denied by Tiny Tikes owner Betsey Grant. “If you believe [my inspection reports], I wouldn’t leave myself with myself after reading my record.”

Since 2021, the Down East Family YMCA Early Learning Center on General Moore Way in Ellsworth has been punished seven times for children being left alone or walking without staff notice.

The facility did not report four occurrences of staff physical treatment and dragging children across the room to the agency, according to state records obtained during a complaint inquiry. The facility has four conditional licenses since December 2021.

“We have invested in additional oversight staff,” Down East CEO Matt Montgomery stated. “We meet with [our licensor] monthly to ensure we are on track and make positive changes.”

Hancock County has 57 registered child care facilities, and Tiny Tikes and Downeast Family YMCA Early Learning Center account for nearly half of all safety infractions.

An inspection report from January 2023 at Driscoll Child Development Center in Portland notes “inappropriate child management” and workers “smacking” a preschooler and grabbing children by the wrist. A staff member reportedly fractured a four-month-old’s arm in the same complaint.

State documents show that personnel did not always file incident reports and could not confirm parent notification. Driscoll Child Development Center has been cited for safety violations since 2020, accounting for 10% of Cumberland County’s 665 safety violations.

Driscoll has been cited over 100 times for safety and procedural infractions since August 2021. The child care program has a conditional license since June 2023 and is renewing.

Driscoll’s Child Development Center received numerous calls, emails, and voicemails from the Monitor and Public Integrity. The owner was unavailable for comment.

Aroostook County, with 80 child care providers, had seven safety violations per provider, more than other counties.

The state averages three per child care provider. More than 10% of safety infractions in Aroostook County occur at Kurioucity Child Care in Blaine. Kurioucity Child Care had a conditional license until May 2023, when it received a full license until 2025.

The Monitor and Public Integrity called. Kurioucity Child Care’s voicemail not receiving messages. No one from the child care program responded.

Many providers in Maine are constantly on the brink of going out of business, said Rebecca Alfredson, director of education at United Way of Southern Maine, and do not have the time or resources to attend additional training aimed at improving the quality of care.

Several providers, including Arrants, the owner of Cribs to Crayons, also said the state’s inspection is extensive. “It’s an inspection of everything. Every kid’s file even if I’ve had them for six years.” Arrants and Tiny Tikes owner Betsey Grant said they felt targeted.

“Writing us up for things that different licensors wouldn’t have written us up for — that’s one of the things that we deal with that makes a lot of people just not want to do it anymore,” said Arrants.

Others, however, disagreed.

Sasha Shunk, the owner of Shunk Child Care in Portland and the chair of the outreach committee for the Family Child Care Association of Maine, said it shouldn’t be hard to keep up with regulations and pass inspections. Her program has frequently passed inspections or been cited for only minor violations.

“I think they can be overwhelming in the beginning,” said Shunk, “but really, if you work with your licensor and use some of the resources that are out there, it should be okay.”

The vast majority — more than 1,000 — of Maine child care providers had fewer than 10 safety and 5 procedural violations between the start of 2021 and July of this year. Almost 500 providers have only procedural violations and 116 have no violations at all.

“I don’t think people go into child care to say, ‘I want to provide poor care to kids’ — that’s never at the heart of the decision,” said Alfredson. “Everyone is in it because they care deeply about children.”

Few consequences, no fines

Despite repeat violations, all of the centers mentioned in this story remain licensed. None has been fined.

Reports obtained by The Monitor reveal that, in many cases, the reasons given for denying or voiding licenses appear similar to issues found in facilities that are still open.

One program, run by Morgan Angers, was denied license renewal in 2023 for “inappropriate child guidance, withholding food for children, corporal punishment, and children rights violations.” Planet Recess Education Center, in Presque Isle, was denied renewal for reportedly shaming, using derogatory remarks and rough-handling children.

As of September, four providers —Tiny Tikes, Bangor Region YMCA, Down East Family YMCA Early Learning Center and Robin’s Nest Child Care — were operating under a conditional license.

Since January of 2021 DHHS has issued conditional licenses to 64 child care providers around the state.

Regulators can impose fines of up to $50 per incident for child’s rights violations and up to $500 per incident for transgressions related to child-staff ratio, disclosing confidential information and giving false information to inspectors.

“While the Department may assess civil penalties when a child care provider fails to comply with applicable laws and licensing regulations, the Department more commonly issues enforcement action, such as issuance of a conditional license,” said a DHHS spokesperson.

Maine’s regulations do not include daily penalties or escalations for repeat violations, in contrast to nearby New Hampshire, where regulators can impose fines up to $2,000 and add daily penalties for ongoing non-compliance.

“These are generally very small businesses that are operating on incredibly narrow budgets,” said Rita Furlow, senior policy analyst at Maine Children’s Alliance. “Fining them isn’t necessarily going to solve the problem.”

Parents left in the dark

Unless the program has a conditional license, providers must display inspection report results but not tell parents of potential infractions or results.

Several parents complained about provider and state contact and follow-up.

Nora Davis (name altered to preserve privacy) told The Monitor her kid started having problems after starting child care at Jo-Ann’s Children’s Center in York County.

Davis said he was scared of sleeping alone or having doors shut and would cower in the corner if told “no” or melt down if his parents left the bathroom. Davis failed to understand what was happening, and her autistic, non-verbal son could not express it.

Many Jo-Ann’s parents informed Davis that their children were scared to be left alone, especially in bathrooms, or ran to the corner when disciplined.

Davis notified the Office of Child and Family Services, which inspected and discovered five staff members reporting shutting children in the restroom “as a form of discipline.”

State regulators ordered Jo-Ann’s to “ensure all child care staff members responsible for, or assisting with, the care of children exercise good judgment in the handling of children” and to “ensure actions that have a reasonable likelihood to be harmful to children are strictly prohibited.”

The plan did not say the child care program shouldn’t lock kids in the bathroom.

Davis was outraged that she was never alerted of the state’s findings and frustrated by the lack of follow-up.

Jo-Ann’s Childcare owner Kendra Gelardi declined to comment on this occurrence.

She said, “It’s really something between the state and the daycare.

York County child care programs, where Jo-Ann’s is located, had an average of four safety infractions between 2021 and 2024, according to Monitor/Public Integrity. Jo-Ann’s operated fifteen child care services, more than most countywide.

In November 2021, Belfast mother Morgan Whitcomb was upset with Kids Unplugged’s response to her son’s child care event.

Staff informed Whitcomb that her son had ran off and was found on the lawn near the child care. Another parent told her later that he had spotted her son screaming in a ditch beside the facility, which is between Route 1 and Belfast Municipal Airport.

“I was in shock, I couldn’t react because all I could think about was ‘what ifs,’” said Whitcomb.

Kids Unplugged self-reported the incident, which the inspection report does not detail. No incident documentation was given to Whitcomb. The Office of Child and Family Services inspector corroborated Whitcomb’s experience. The office issued a proposal. Kids Unplugged was also given a conditional license for violating state laws.

A staff member threatened to punish a child and a video showed him “shove the child, pick the child up and slam the child down on the sleep mat.” Further infractions were detected at Kids Unplugged. Two staff members saw another leave children alone two to three times on the playground in the past month, according to the report.

Kids Unplugged has been inspected seven times since the incident, but solely for procedural breaches like missing fire drills.

“I had to quit my job and pull him out of the daycare because there were no other daycares open,” Whitcomb said.

Calls and voicemails from the Monitor and Public Integrity were many. No one from Kids Unplugged responded.

The Monitor reported that several parents were unaware that their child’s daycare was on state notice.

“I never knew about the conditional [license],” Whitcomb added. The community knew about the incident through word of mouth, but that was it.”

Other parents sought direct notification of self-reported occurrences or state inspection findings.

“Daycares have many papers. Davis admitted that as a father, he would not notice the inspection report hanging on the wall when he entered.

Hammes of DHHS stated in an email that “Every complaint or report receives a response, though it may not be in the form of follow-up with the complainant.”

In contrast, New Hampshire requires facilities with conditional licenses to “immediately provide the department with evidence that the program notified all of the parents of enrolled children of the conditions imposed on the license by the department.”

“There’s a notice on her door that she failed inspection, and then that was it,” Davis said. “After the violations were posted, I never heard from anyone again.”

This report was written by Investigative Reporting Workshop members Hannah Campbell and Lillian Juarez.

Leave a Reply