JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. (KMIZ)

Legal experts say that mandatory jail time and what jurors are told to think about could affect how a new state law on car chases with police is used for the first time.

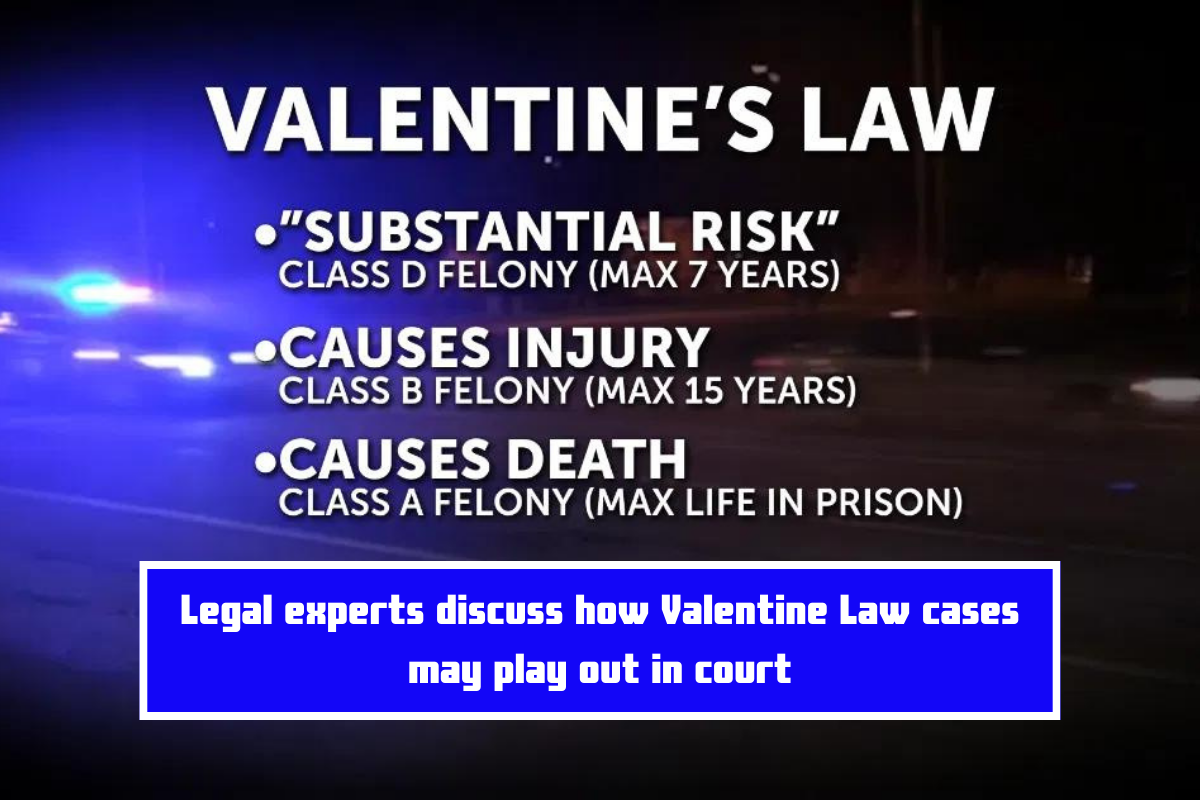

This session, lawmakers in the state passed a law called Valentine’s Law, which lets prosecutors think about charging people with excessive fleeing a stop.

If someone drives away from police who are trying to stop them, they could be charged with a class D crime and have to spend a year in jail if they are found guilty. If someone gets hurt or dies during the chase, the range of punishments gets bigger.

Since August 28, when it became law, at least two prosecutors in Mid-Missouri have used the new law. Christopher Wehmeyer, 23, was charged by officials in Camden County with evading police who were trying to pull him over for speeding.

A crash on Highway A killed Osage Beach police officer Phylicia Carson. She had lost control of the car. In Boone County, a man was charged with hurting a state trooper when he drove over the trooper’s spike strips while being chased on Interstate 70.

One important part of the new rule is showing that the person who is running from the police posed a “substantial risk” to other people. The head of the Missouri Office of Prosecution Services, Darrell Moore, told ABC 17 News that the new rule makes traditional chases more dangerous.

People who were suspected were often charged with resisting arrest, a class E felony that can get you up to four years in jail. People might not try to get away from cops if they know they will have to go to jail if they are caught.

Moore said, “Hopefully word will get out on the street and people will realize that this isn’t the old days where I could run from the police and get a slap on the hands. This is serious prison time.”

T.J. Kirsch, a lawyer for the defense, said that the required jail time takes away judges’ freedom to choose sentences.

It’s possible that the fear of jail time will help prosecutors make plea deals on less serious crimes. He said that judges usually know more about each criminal case than the lawmakers who set the required time.

“The discretion for the courts is gone as soon as there is a substantial risk to anyone else,” he said. “That’s without regard to the length of the pursuit, how that substantial risk is proved, what that substantial risk is.”

Aggravated fleeing a stop charges can be brought against someone who drives away “at a high speed” or in a way that poses a “substantial risk.” Moore and Kirsch both said that there are different ways for prosecutors to show that risk.

“It could be: Are you in the other lane? Are you crossing all over the place? Are you going through people’s yards? “You can look at that; that’s the kind of thing a prosecutor would say,” Moore said.

One of the parties in the case—either a judge or a jury—will decide if someone’s actions while running from police caused someone else’s harm or death. Moore said that the jury will be given directions with answers to these questions when they are deliberating a case.

But the fact that the person is running away from cops probably won’t affect how they decide what to do.

“There’s no room for speculation about ‘Did he mean to kill or hurt someone? Was his actions the direct result?'” Moore said, “That’s not necessary.”

Kirsch said that higher courts probably won’t change a ruling just because there are arguments that question those connections.

“The bar for causation in a criminal case is pretty low, it’s going to be heavily reliant on the fact-finder, whether the judge or jury thinks the flight is the cause and is unlikely to be second-guessed by any reviewing court,” said Kirsch.

They also have to show that the suspect knew or “reasonably should have known” that a police officer was trying to pull them over.

Kirsch talked about the case against Sergei Comerzan in 2015 in Audrain County, where Troop James Bava of the Missouri State Highway Patrol died while trying to pull him over for speeding.

A jury found Comerzan not guilty because he said he didn’t know Bava was trying to pull him over.

“If you’re miles ahead going way too fast on a motorcycle, the wind blowing, the engine roaring, then it’s reasonable to say this person just didn’t know there was an officer trying to catch up with them,” said Kirsch.

The prosecutor for Boone County, Roger Johnson, said that his office will “generally recommend the maximum sentence and oppose probation for high-speed chases” in most cases.

Leave a Reply