Missouri’s general revenue has trailed inflation for two years. That disparity is widening, so the next few months could determine whether state revenue declines for the first time in almost a decade.

“September is a good sort of bellwether one for us, because that’s where we get quarterly payments from both individuals and corporations,” Gov. Mike Parson’s budget director Dan Haug told The Independent last week. There are few notable due dates in July and August, so we don’t look at patterns until September.

General revenue revenues are down over 3% from fiscal 2024 through Friday.

The federal Bureau of Labor Statistics reported 2.74% revenue growth and 3% inflation in fiscal 2023. Revenue rose 1.47% in fiscal 2024, which ended June 30, while inflation remained at 3%.

A recent Pew Charitable Trusts analysis found slow revenue growth in several states, including Missouri. Many states, including Missouri, saw revenue spikes during the COVID-19 pandemic, spurring expenditure and tax cuts.

Missouri had double-digit revenue growth for two years until early 2023. Nationally since fiscal 2023, state government revenues have slipped below inflation and pre-pandemic growth, the research says. That’s the first time in 40 years without a recession.

“There’s less fiscal flexibility, but it’s unclear whether states will be really under strain or not, but it’s going to be more difficult than before,” said research author Alexandre Fall, a Pew senior associate.

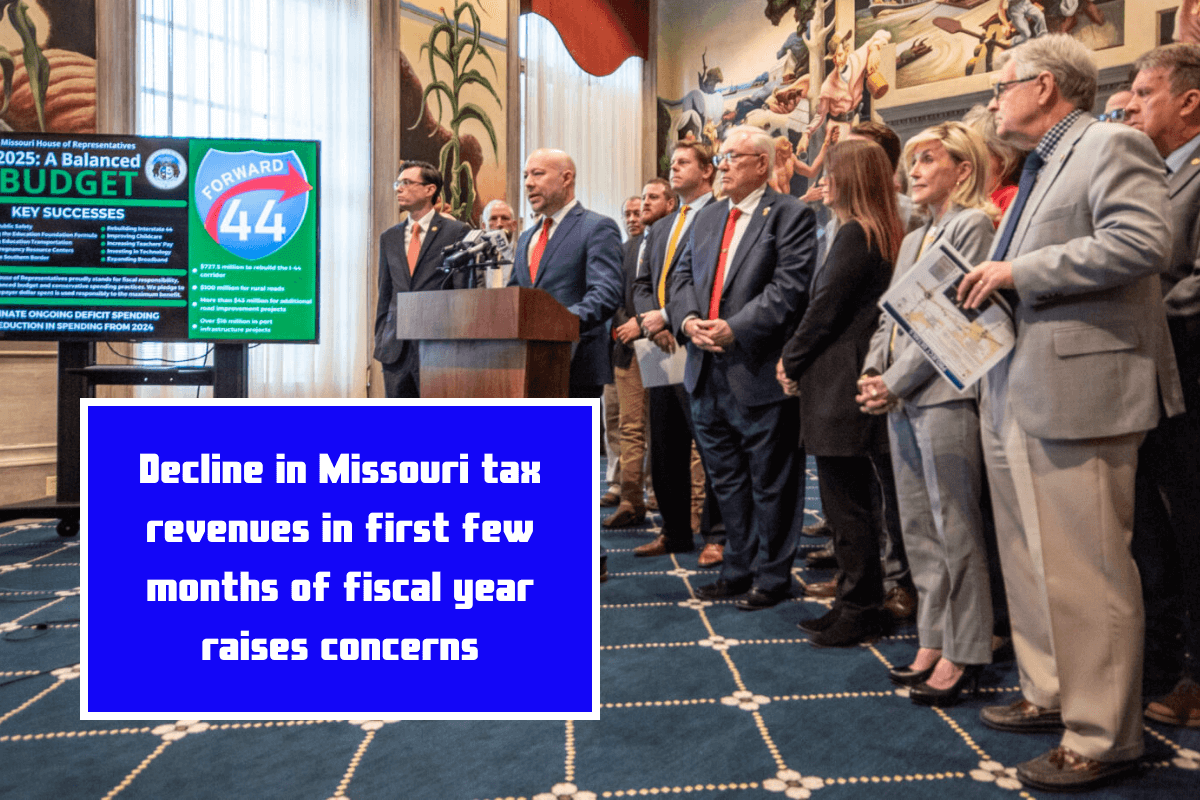

The Republican-led legislature tried to limit general revenue expenditure to $13.2 billion in this year’s budget in spring. The budget projected spending $15.1 billion in general revenue, drawing off surpluses from the 2021 and 2022 surge, despite Gov. Mike Parson’s veto.

House Budget Committee Vice Chairman Dirk Deaton, a Noel Republican, said lawmakers must limit spending to new revenue.

“If revenue is lower in the future, we will have to look carefully at core spending items to make sure the state budget is sustainable and Missouri is well-positioned to balance the budget year after year,” Deaton said.

State revenue was down early in fiscal 2024 but grew somewhat, Deaton said.

State Rep. Peter Merideth of St. Louis, the Budget Committee’s top Democrat, said future legislatures should prioritize state needs above surpluses. Term constraints prevent Merideth from returning to the House.

Merideth projected education programs will suffer from revenue-based budget cuts rather than state resources.

“We will cut education further,” he declared. Maybe it’s on the transportation line, or maybe it’s somewhere else, and we’ll slash higher education because those are the only two fairly discretionary locations the legislature has to cut with huge sums of money.”

Missouri sitting on a state budget surplus

The general revenue fund has $4.8 billion on June 30, down $960 million from last year. This is the third-highest state year-end balance ever.

Some of that money is in multi-year projects like a $300 million Kansas City mental health center, but most is unencumbered.

Some extra money was stored elsewhere. The state holds $2.4 billion from general revenue for significant projects like repairing Interstate 70 and expanding the Capitol Building.

Another $1.8 billion was in ordinary revenue-spendable accounts.

Liz Farmer, a Pew fiscal policy researcher, said lawmakers and state officials must spend surplus funds without depleting them.

“States are spending balance dollars rapidly,” Farmer added.

Parson’s January budget predicted a $1.9 billion unencumbered general revenue balance by June 30, 2025.

Lawmakers have utilized the surplus to pay district projects and smaller items in the past two years. In 2023, Parson trimmed $550 million off the budget and authorized $1 billion this year, vetoing several of those items.

Merideth advised future lawmakers to avoid district funding. Stagnant or falling state revenue should mean greater cash for essential program gaps.

“We have a surplus to work with in the short term but we haven’t hit an economic crash, which eventually will happen,” Merideth remarked. “That’s when we’ll have problems.”

Revenues dropped from $8 billion to $6.7 billion during the 2008 crisis. Haug, who has served in the legislature and executive branch, said the state is recession-ready.

“We’ve got a very healthy fund balance to help us get through a minor downturn, if there is one, although I’m not sure there will be one,” Haug added. “We’re in a lot better spot to weather this kind of stuff than we have in probably any of my time here.”

Due to revenue growth, state government costs have changed permanently.

Parson’s pay rise plans raised the pay of every state worker employed before 2022 by at least 20.7%. A longevity pay plan adopted this year, increases in night pay for jail, mental health, and other custodial personnel, and a $15 minimum compensation for all public employment have given certain workers far higher percentage rises.

State agency staff vacancy rates average over 10%, so adding workers will raise state costs.

Fall stated “increased state employee pay and salaries, as well as permanent tax cuts, were two very popular policy choices that were made across states and in Missouri.” “But now that we’re seeing all this excess revenue pull back and states have less flexibility, it’s unclear what comes next.”

Missouri’s 2022 special session income tax rate cuts and 2023 Social Security benefit exemption measure were major permanent tax cuts.

The proposal will cut state revenue by $1 billion or more yearly. The highest income tax rate will drop to 4.7% on Jan. 1 as part of the 2022 tax decrease phase-in.

Deaton said those cuts will boost economic activity and revenue.

Through our tax policy, Missouri has made it plain that we are more interested in building people’s bank accounts than in bringing money to Jefferson City, he said.

With a new governor and parliamentary leadership in January, tapping the excess may be tempting.

“Whoever is in that governor’s mansion and whoever is in the budget committee chair will make a significant difference and it’s hard to predict,” Merideth added.

Missouri’s revenue outlook

Missouri general revenue collected $9.6 billion in the last fiscal year before the outbreak. The fiscal year ending June 30 totaled $13.4 billion, up 1.47%.

Personal and corporate income taxes fell in fiscal 2024, two major state revenue sources. This year’s revenue reduction has extended to sales tax receipts.

Sales tax rise led the way as consumers spent federal pandemic relief funds and salaries and prices rose, causing the highest inflation rates in 40 years.

Haug said there is no evidence in the Missouri economy that the sales tax drop is permanent.

“People may be pulling back a little bit temporarily to pay off debt and things like that, but eventually the fundamentals will drive it,” Haug said.

Missouri created 62,400 jobs from July 2023 to July 2024, and first-quarter personal income climbed 6.7%. State GDP is increasing 1.6% annually, and while inflation is slowing, prices are up 2.5% nationally.

“Long term, that’s what’s going to drive our revenues, and I think that’s still true,” Haug added.

Farmer said people are spending more on non-taxed services and travel and buying cheaper goods since pandemic restrictions ended.

Missouri forecasts revenue for the remainder of the fiscal year and next year in December. She claimed extended fiscal outlooks would prepare the state for problems.

“That is one of our key benchmarks for state fiscal health, and something that could be really helpful for assessing what these impacts on personal income tax and those cuts look like for the state down the line for revenue,” she added.

Deaton suggested a longer-term perspective, but experience demonstrates that short-term projections are inaccurate.

“They were very close and other years when estimates missed badly,” Deaton added. “The farther you extend, the greater the margin of error.”

Leave a Reply